This article covers the history of the Toronto Nature Stewards from its origins to 2024. It is a success story. TNS has grown from eight pilot sites with 150 Stewards in 2021 to 43 sites and over 900 Stewards working in the 2024 season in teams led by 135 Lead Stewards we have trained for the work. To help ensure all of this is manageable and coordinated, we now employ a small staff of three people. Our growth and success are clear. It took a lot of hard work by volunteers. It has been quite a journey.

Origins

It was 1977. Professors Bob Jeffries in the Botany and Roger Hensell in the Zoology Departments respectively of the University of Toronto (U of T) decided to undertake a unique scientific study, the 1977 Toronto Ravines Study (available in Weston Family Library in the Toronto Botanical Gardens, or upon request from TNS).

The study was unique because it was the first baseline study done in an urban natural area in Toronto using scientific methods like standardized plots. Most university research of natural areas had previously focused on more remote and pristine forests and natural areas, not the heavily disturbed patches of green here and there in cities and towns. Previous studies of Toronto’s ravines and natural areas were wonderful descriptions of what was observed at the time but lacked the scientific rigor of a full baseline study.

The 1977 study was also unique in being promoted by and funded through private funds raised by non-academic Toronto residents Paul Scrivener and Dale Taylor. They were Toronto ravine activists, themselves co-authors of a previous amateur ravine study (Park Drive Ravine Study, 1976, Toronto Field Naturalists) done with fellow volunteer naturalists as one of a series for Toronto Field Naturalists (TFN) at the time. The study benefited from the encouragement and advice of then TFN leader Jack Cramner-Byng, and a memorable ravine visit with ecologist Dr. Jack Livingston, who accompanied the volunteer TFN team one day into the Park Drive Ravine. Helen Juhola and Erna Lewis, who did the botany, were on every field visit. Other contributors were Michael Goldstein, Michael Hough, Eric Nasmith, and Ron Tasker.

In the next three years, Scrivener went on to be instrumental in the City of Toronto’s adoption of its first Ravine Protection Bylaw. Throughout this period, Scrivener and Taylor were prompted by increasing private and public incursions onto and into ravine lands, and emphasized at meetings with local ratepayers that there was a need for private ravine owners and their neighbours to step forward as volunteer stewards to help protect their priceless natural heritage, or it would steadily deteriorate from human disturbance.

Toronto Ravines Revitalization Study, 2015-2018

The 1977 study gathered dust on the shelf for the next forty years as Scrivener and Taylor pursued their professional careers. Then, in 2014, they agreed they should find some way to have a new study done to revisit the 1977 study and determine systematically what had happened to nature in the ravines in the 40 years after the U of T baseline study.

Fortuitously, the City of Toronto also had begun land-use planning consultations to assist in the development of a Toronto ravine strategy. Two of the key themes eventually emerging from those consultations were the priority to protect nature in the ravines and the key role for volunteer stewardship in doing so.

During the city consultations Scrivener and Taylor met four other people who keenly shared their concerns about the threatened natural state of Toronto’s ravines: Dr. Sandy Smith, a professor of forest health in the U of T Forestry Faculty; Eric Davies, then a doctoral student in Forestry; Anqi Dong, Master of Forest Conservation student; and Catherine Berka, a resident active in issues in South Rosedale, including ravine-related issues. The six realized that they had mutual interests in preserving urban nature based on sound ecological science and began to meet at the Faculty of Forestry offices at the U of T to consider some kind of ravine-preserving initiative.

The meetings of this small group gave birth to the Toronto Ravines Study: 1977-2017: Long-term Changes in the Biodiversity and Ecological Integrity of Toronto’s Ravines. Funded by private donations combined with student academic assistance, and eventually gaining its own website, TRRS was conducted by graduate students Eric Davies and Anqi Dong, with contributing studies by Alex Stepniak, Joey Kabging, Jane Michener, and Jack Richards. The study replicated the 1977 baseline study of the Rosedale ravines with its standardized plots and systematic methods. Beginning with field work in 2015 and ending in 2017, with everyone pitching in on the written final report and slide presentation, the study was officially released in 2018. (To read the full study, see here.)

The TRRS study findings were alarming. The forty-year comparison revealed a striking deterioration in forest health, with invasive non-native plants overtaking native species in many areas and even in the deeper woods, where non-native Norway maples increased from 10% to 60% of tree cover in the ravine areas studied. Norway maple is a street tree that replaces the diverse native forest ecology by casting deep shade supporting only its own saplings. Alas, it is a street tree once deliberately planted in our ravines by the city because it is fast-growing.

The TRRS working group then turned to a considerable effort to raise awareness of the 2018 TRRS study. In the event, it received significant local and a degree of international coverage (see website). It was also presented by the TRRS group at the first of what has become a series of well-attended public symposia on Toronto’s ravines organized by and with the Toronto Botanical Garden.

The TRRS group joined other deputants, such as the Toronto Field Naturalists, in making presentations to the Environment Committee of Toronto City Council, as the city moved toward and adopted its new Toronto Ravine Strategy in 2020 and later its Biodiversity Strategy. Although the city’s policy framework listed preserving nature as the first ravine objective, it also covered several other objectives for the ravines, including significant increases in public use, trails and access—objectives which received most of the proposed new city funding. The TRRS group emphasized that the primary priority for the ravines should be to preserve nature in the first place, based on ecological management frameworks, or there would be less and less of it in a healthy state for the public to enjoy and derive other ecological benefits from.

During this period, the group was frequently using the phrase “ecological integrity” as its key ravine restorative concept. This came up against the views of some at the city and a few dissenting experts that the concept was inadequate for properly understanding and managing city ravines and natural areas because of its sole reference to native plants as the basis for maintaining disturbed urban natural areas. One went so far as to say that invasive weeds in disturbed areas should be regarded as valuable “cosmopolitans.” As “ecological integrity” became a somewhat charged wording in discussions with the city, the group began to back away from use of the term as such, though it continued to maintain its underlying native species-based ecology approach in assessing and treating the deteriorating condition of the ravines and other urban natural areas in Toronto. That and funding limitations in turn led to some post-study tactical differences, and after his good work on the study, Davies departed the original group.

TRRS to TNS

One of the main recommendations of the TRRS study was for a new stewardship effort to make up for the city’s inability to do all the work needed to preserve urban nature. The original TRRS group now focussed on what that next step should be to get a serious volunteer effort organized.

Several first steps were undertaken in getting community-led stewardship efforts underway to the point of doing actual remedial work in the ravines.

One step was to ensure the work of stewards would be based on sound science and up-to-date information about identifying what is harmfully invasive, removing the invasive plants in the best way, replacing them with native replanting, and thereafter systematically monitoring the ecological results. This led to the idea of a manual to guide and provide a basis for training volunteer stewards. Pat Concessi had joined the original leadership group and undertook the preparation of such a manual, which actually became two manuals—one for stewards of public ravine lands and a second for private ravine owners—accessible via the public lands and private lands portals on the TNS website. With input from various experts and others in the group, now joined by Paula Davies, who was already a nature leader best known for her leadership at Todmorden Mills Wildflower Preserve. Pat worked tirelessly to get the manuals produced. These would form the basic reference for the subsequent training of TNS Lead Stewards. Since 2021, training of Lead Stewards who head volunteer teams at TNS sites occurs in sessions preceding each growing season and a convivial wrap-up session at the end of each season.

The manuals and training initiatives were a key factor in the second of the essential first steps: the challenge of getting the city to permit volunteer stewards to work in public ravine lands and natural areas without direct city supervision. We knew this would multiply nature-protecting remedial work far more than the city alone could deliver via staff within its budget through its Parks, Forestry and Recreation Department (PFR). Previously, the city’s use of volunteers had been scattered and short of full-scale remedial work. Our slow but steady progress with the city provides textbook lessons for active naturalists to be clear and precise in your “doables” and “asks” and to be very patient but persistent as municipal staff work through many often-conflicting pressures in responding to any one set of initiatives to change the status quo. Even if you increase the awareness of and receptivity to your urgent message at the political levels of the powers that be, as we also did, change in the system takes time.

The third initial step needed to organize the new stewardship effort to save Toronto’s ravines was to reconstitute the original leadership group as a distinct entity. We became the Toronto Nature Stewards, with the help of new members already working on restoring nature in Toronto: Clyde Robinson, a leader of efforts to preserve nature at Ashbridges Bay; and Andrew Simpson, who was already actively stewarding a natural area.

The TNS name and a logo were decided. The name was important, because the original ravine group realized in discussions with others that the scope of the organization and volunteer effort should include both wooded and other mixed-use natural areas outside the ravines, including major city parks, like High Park, and parks along Toronto’s shorelines, such as Ashbridges Bay. Hence the name “Toronto Nature Stewards” (TNS) was adopted in 2020. The signature treed logo came out of deliberation over several suggested designs and with some professional advice—again an effective group product.

Under the lead of Simpson, a distinct TNS website was established. It wasonly previously nested within U of T Forestry and readily confused with other sites. The site was developed in an agreement with Jason Ramsay-Brown, a former TFN president and another one of Toronto’s most active naturalists.

Subject to occasional direction from the Leadership Group, an Operations Group emerged to coordinate work actually being done to select sites and assist stewardship on sites under the tireless efforts of Concessi and Berka. An annual round of stewardship activities began to emerge, including agreement with the city on sites and permitted work on sites for each upcoming season, training of Lead Stewards and recruitment of Stewards for the seasons work on the sites and the undertaking and reporting of the actual work done. Each season began and ended with a well-attended Lead Steward event. Each year, the City allowed a wider scope of TNS work toward our goal of not only removing invasive species but replanting with native species.

The Funding Story

Securing private donor funding, a feature of the original 1977 study by Scrivener and Taylor, was essential to TNS progress from the beginning. Private donations can give both funding certainty and sufficiency and a scope for independent action which government funding often cannot assure.

We began by contacting ravine neighbourhood residents and literally went door to door, circulating pamphlets and meeting homeowners in and around the inner Rosedale and Moore Park ravines featured in our initial Toronto Ravine Revitalization Study. This produced several generous donations and most of all engaged the interest of Martha Rogers, who became our largest funder.

Martha Rogers lived along the ravines in Moore Park and already had an active interest in preserving the state of nature, including her recently requesting a TRCA study on the state of nature in her local ravines.

When we dropped a leaflet at her door, Martha immediately got in touch and then picked up the substantial remaining balance of our TRRS funding target. That ensured the TRRS study was completed, and we could continue on the ground with TNS volunteer operations. Following that, every two years in our TNS donor funding campaigns, Martha has donated the majority of our funds.

As well as her concern about protecting Toronto’s urban nature, Martha told us a key reason for her major TNS funding role was and is her dedication to charitable purposes that actually do something and do it cost-effectively. We have kept Martha closely informed on what we are spending and doing with hers and others’ donations. As with other donors, Martha continues her donations because TNS has delivered well in terms of demonstrated high value for donor-dollar for a terrific purpose.

We have also benefitted from many other donors who have valued our practical and cost-efficient TNS efforts to preserve nature in Toronto, including three other major TNS donors: The Dalglish Family Foundation, the Schwartz- Reisman Foundation, and an anonymous donor.

Successful U of T Working Relationship

As with any volunteer effort, it helps to have a strong institutional partner. The relationship between TNS and the University of Toronto has been and will continue to be a fundamental part of the TNS community-led ecological restoration purpose and its success story. From the outset with the TRRS study done by Forestry students under academic supervision and through the formation and early years of TNS, U of T Forestry—specifically the Urban Forest Lab under Professor Sandy Smith—has provided key inputs in student research and TNS staffing while serving as the TNS funds holder and financial administrator. When TNS must specify an official location, it is the address of U of T Forestry, thoughForestry has since gone from its own faculty to become an institute in the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design.

Since the outset, Smith and Berka have worked out effective and accountable informal processes that have made this relationship function effectively through each year as funds are donated and expenses incurred for the common charitable purposes of the relationship. Donors receive charitable tax receipts and are reassured by the U of T affiliation.

Since TNS is a significant achievement and ongoing effort in community-led ecological restoration, it is essential that the current excellent working relationship with U of T Forestry becomes a permanent partnership.

Working with the City Government

The city government is not the only public player. The Toronto Regional Conservation Authority (TRCA) owns most of the public ravine land in the city to control flooding and issues permits for the city to manage it. Together, the City of Toronto and TRCA regulate land and water use, undertake infrastructure emplacement, raise urban nature awareness, and facilitate specific volunteer groups for given projects in some ravines and natural areas. Their longstanding “hands off” approach with respect to natural areas in Toronto is to prevent any alterations, including removing and replacing any plants and trees, other than public projects they themselves undertake and supervise. Our partnership represents an emerging direction towards public engagement.

Staffing

With its fast growth, TNS has had a workload exceeding even our most committed volunteers. Beginning in 2019, and with Smith’s cooperation, we began to bring into the organization a few trained forestry students and graduates to help with the communications and coordination needed to serve and grow our stewardship base and get us through the annual round of activities before, during, and at the end of each season. This is all climaxed by the end-of-season gathering of Lead Stewards, now organized and facilitated by our TNS staff—see photos on our website. Staff have also taken leadership of equity and inclusion initiatives at TNS so that our organization can continuously reflect the diversity of Toronto.

Working With Private Owners

Early on, TNS leaders realized that much of urban nature in Toronto is under private ownership. Indeed, some were themselves owners of ravine land. After more than 200 years of urbanization, the Toronto ravines alone still cover 17% of the city, collectively totalling over 11,000 hectares, of which 40% is privately held.

It was therefore important to engage owners of private property who had some of their property still in a natural state adjoining public lands that together form an overall ravine or other natural area.

To address this challenge, TNS developed a private owners natural area manual along with the manual applicable to public lands. The manual is attached to a separate portal on the opening page of the TNS website. Private owners can check out this part of our website and contact us to get further advice.

In some cases, a private owner cooperates in TNS projects and events. For example, in 2018, the president of the University of Toronto approved an early TNS event and tour of the ravine land forming part of the president’s official residence on Highland Avenue. The tour revealed the extensive growth of invasive plants on that section of the Park Drive ravine behind the president’s residence. Subsequent work on the property has begun to address the problem.

Networking and Partnerships

Through our communications and outreach, helped in some cases by cross-memberships and appearances at various nature events, TNS has linked with other nature organizations in the city to widen our consultation in site work, and on occasion to advocate with the city government on common issues.

The communications effort has been aided by excellent graphical material and pamphlets produced by staff that we circulate at public outreach nature events across the city.

An intentional effort has been made to reach out to the Indigenous community. TNS leaders have met with Indigenous nature leaders at Indigenous natural sites on several occasions and have received Indigenous input to our manuals and operations. We maintain links with other site-specific groups, where several, such as Glen Steward Ravine and High Park, are already well established. We also cross memberships with groups like TFN. Our U of T relationship also taps into the wider academic and research community on urban nature-related scientific developments.

TNS has periodically appeared at City Council committees as a deputant along with other organizations like TFN to comment on proposed city initiatives and raise awareness of TNS activity. Several such appearances occurred during the City Council’s deliberation and adoption of the Ravine Strategy and the Biodiversity Strategy. These appearances were assisted by a repeated effort to ensure City politicians on key committees and across various city wards were made aware and hopefully supportive of TNS purposes and activities. If any group, including TNS, needs to press for changes and adjustment in public policy, increasing the awareness of the situation at the political level can offset reluctance of regulating bureaucracies to a change in their approach.

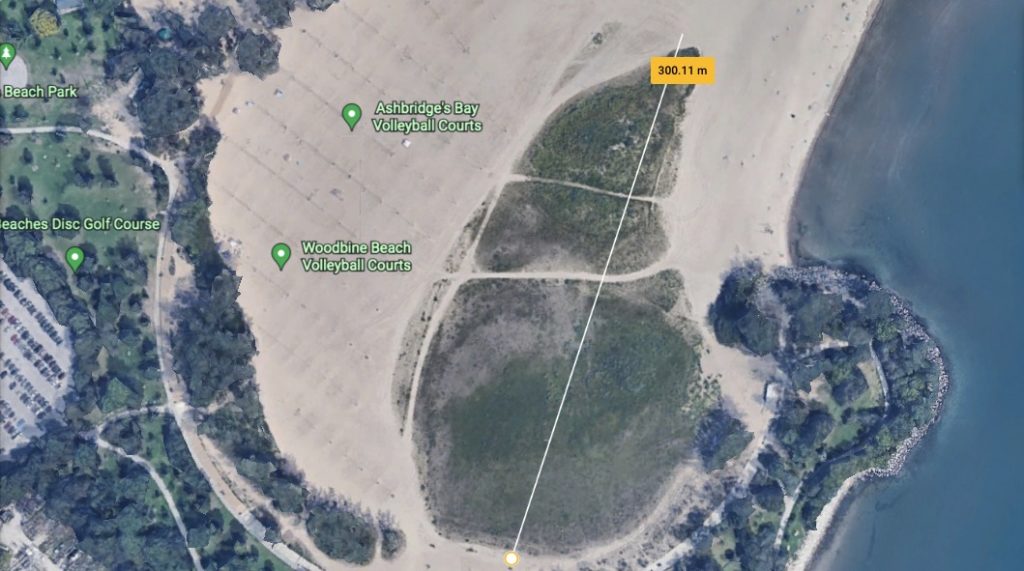

To be clear, TNS is not a nature advocacy group as such—our emphasis is doing actual remedial work in ravines and natural areas. However, we certainly add our voice in natural area situations where nature is threatened altogether. A great example of that was adding our name to a big effort led by nature stewards to leverage city-wide naturalist influence in response to a situation that arose in Ashbridges Bay. The city had approved with little consultation the insertion of a disk golf course. A large group co-led by TNS Lead Steward Clyde Robinson successfully pressed the city to reverse its decision and to continue preserving the Woodbine Beach Dunes Ecosystem natural area.

Informal Status

During the history of TNS thus far, questions about continuing its informal status have been carefully researched and considered at various points. The fact is, with the U of T working arrangement via Professor Sandy Smith providing us with charitable status for donations, financial processing, and staff arrangements, TNS has achieved a great deal while remaining an informal group. This has also meant that TNS has avoided the extra administrative burden and costs of becoming a formal non-profit organization, as well as the legally vertical structure under a Board of Directors and a formal set of directive by-laws that a formal non-profit would mandate. This has freed us to concentrate our mission and efforts to develop and manage our stewardship operations. It appears feasible for us to operate with this informal flexibility for at least a while longer, depending upon our longer-term requirements.

2024 Checkpoint and TNS Reorganization

By 2024, TNS had reached a size requiring a reset in terms of how we were organized to deal with the workload. Some of our volunteer leaders were simply overworked and responsibilities needed to be better defined and distributed throughout TNS.

TNS proceeded with a third-party study of our structure and functioning, conducted in a project with the Ontario College of Art and Design University (OCADU) via Stephen Davies, a recent addition to our Operations Group. After a few stages of reporting, TNS decided to adopt the recommended decentralized “sociocracy” approach, designed to ensure equal voice and to effectively distribute responsibilities throughout the organization (see TNS website for our new organizational structure of Circles). The TNS leadership group and many TNS Lead Stewards participated in the study process. The OCADU Strategic Foresight and Innovation student team included Emilio Castillo, Vandana Jagannathan, Mariel Mading, and Paulina Rousseau.

The recommended changes were thoughtfully discussed, inspiring some action and enabling some overworked leaders to step back to less burdensome responsibilities, promising a good way forward for TNS as it continues to carefully grow its size and capabilities. As with all volunteer organizations, there must be periodic checkpoints and in 2024 TNS benefitted from this very extra-useful assistance from others on a voluntary basis.

The season ended with another great Lead Stewards gathering at the Brickworks at which Concessi was awarded the first TNS Outstanding Achievement Award for her many contributions to making TNS an early success. A medium- and long-term strategic planning process was also begun that will draw on and be developed from everyone’s views throughout our equal-voice informal organization.

TNS Outlook and Challenges Beyond 2024

After TNS reviews and strengthens itself at the 2024-25 checkpoint, we will be in a good position to continue carefully growing our stewardship base and the number of sites across the city where TNS is at work preserving nature. We all feel that we want to grow, but such growth must not exceed our ability to enable it, to coordinate it, and to distribute responsibilities in a fair and manageable way.

One of the keys to continued success at TNS will be our carefully developed continuous monitoring system as it begins to disclose the ecological results of our volunteer invasive removal and native replanting efforts. It will be based on reports received from Lead Stewards across the city. Such monitoring and subsequent adjustments in our work indicated by the monitoring will fill the final gap in what we hope will be a fulsome and permanent new volunteer presence in restoring Toronto’s urban nature.

TNS is always prepared to share the lessons we have learned in our own experience and early history. Anna Meng, staff ecologist, has given talks at community events with groups like Toronto Community Housing. She has also given numerous presentations at academic conferences like the Canadian Urban Forest Conference and the Ontario Invasive Plant Council Conference. Following these appearances, TNS has received requests from other cities to provide interested nature volunteers a readily transferable platform of the start-up steps we took and what we have learned works well to guide similar efforts.

Our early TNS history demonstrates that volunteer commitment, energy, and determined work together can gain the support of public authorities and regulators for multiplying the human effort needed to preserve much-disturbed and threatened urban nature. We will thereby continue to retain and enjoy the huge value we receive from our public and private natural assets.

—R.D. Taylor and Paul Scrivenor, with input from the co-founding TNS leadership team.